Another Virtually Unreached Tribe

To understand the challenge before us, let me give you some background.

Along the eastern border of Pakistan live a tribe called Marwari, whose 8,300,000+ members span the border into India. The Marwari occupied this territory long before India was India, stretching from Iran and Afghanistan in the west to Myanmar in the east. Religious fighting between the Hindus and Muslims, of which Mahatma Gandhi was a casualty in January 1948, caused India, in August 1947, to cede their primarily Muslim territory in the west, called Punjab, to form the country of Pakistan. Then, in March 1971, their Muslim territory in the east, called Bengal, was ceded to form the country of Bangladesh. Conflict persists and, at times, erupts, though both nations work tirelessly to control it. Still, though warfare is subdued, prejudice continues.

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by an extremist Hindu who felt Ghandi’s tolerance for the Muslim population, ultimately resulting in giving away the territory of Punjab, was treasonous to Hinduism and the Hindu population of India.

When Pakistan and India were separated in 1947, millions of Hindus and Muslims became refugees. Most of the Hindus in the newly formed Pakistan (and Bangladesh) fled to India, but some of the lower castes, such as the Marwari, chose to remain in their homeland and freely cross back and forth. The partition did nothing to ease the ancient antagonism between the Muslims, who now comprise most of the population, and the minority Hindus, who are less than two percent of the population.

The Marwari tribes are traditionally considered an “untouchable” caste by the caste-conscious Hindus. That stigma, though not officially recognized in a Muslim culture, still persists. The people are very poor and have little or no possessions. They are subsistence farmers and survive having little rain and living in mud-block homes with dirt floors and typically with no electricity, water, or bathroom facilities. The five wells we dug were in “converted” villages of the Marwari. Having water to drink, wash, and irrigate their fields has dramatically increased their standing.

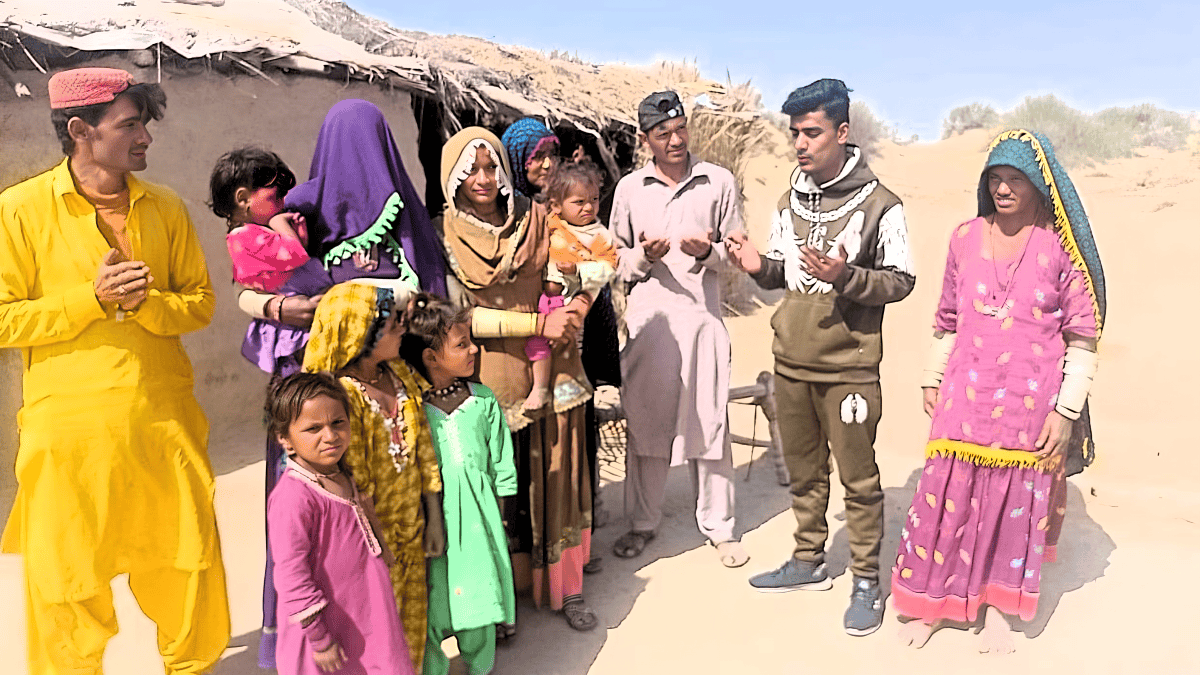

Marwari children and ladies pose to wave hello.

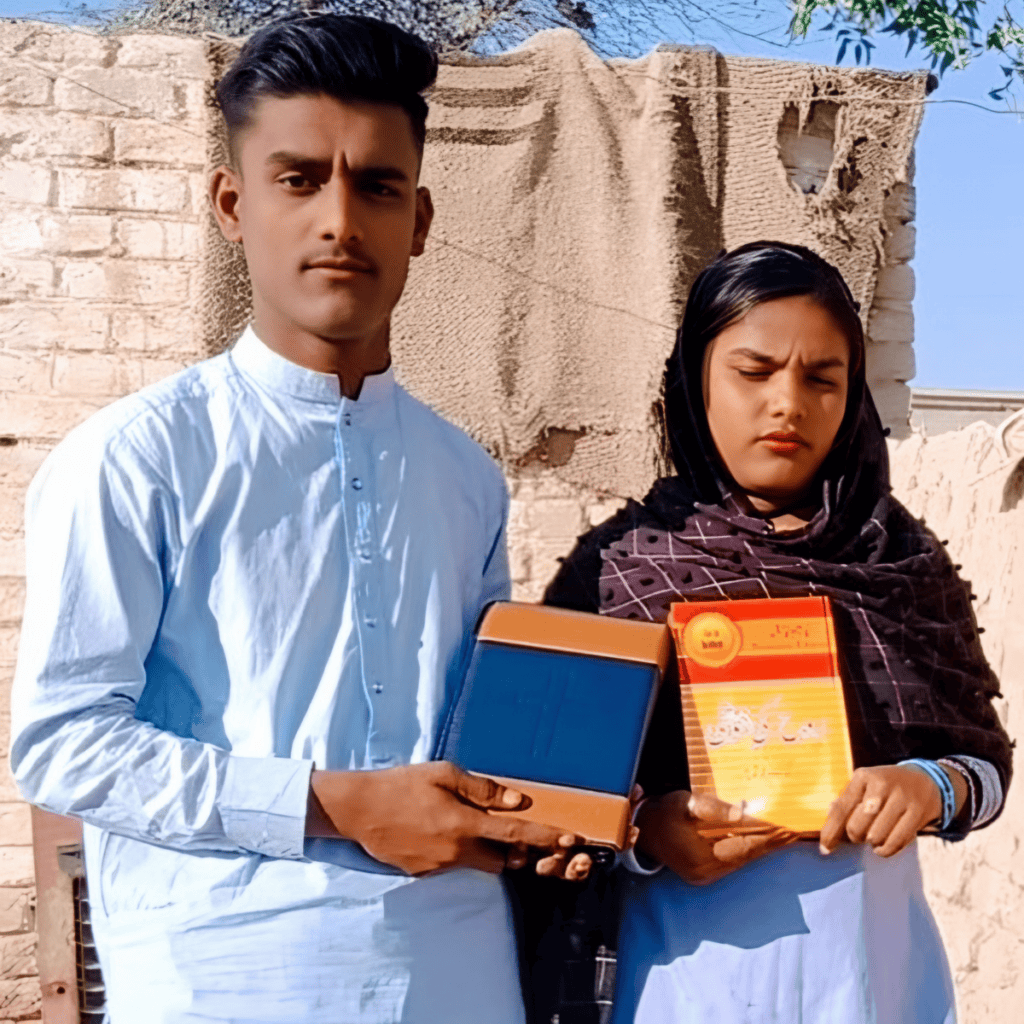

Rajeva Gee, a Bible Institute student from the Marwari tribe has started three churches within his first year of salvation. Here, he gives a Bible to a new convert. She holds the Bible which the Great Commission Fund provides, and he holds a hand-made leather cover the members of the church and institute give as a gift to each new believer.

What is the Religion of the Marwari?

The majority of the Marwari who live in India are Hindu. One-sixteenth of the Marwari live in Pakistan and are a mixture of Hindus and animists. As the title of the article states, they are a primarily unreached group. The majority, about 15 out of 16, live in India and have spread all over the country. Being educated, they have high positions in business and government; however, their cousins in Pakistan, separated for nearly eight decades, are poor farmers who scratch out an existence in a desert region. It is this branch of the Marwari tribe that we are targeting.

Though religious tolerance is practiced and highly revered as a tradition, the Pakistani government has little tolerance for Hindus and, particularly, Hindus of lower standing, such as the Marwari. As an example:

In December, we revisited a village where we had installed a well two years earlier. The people were delighted and happy to see us again. We had to leave the village before the darkness swallowed us up, and I commented on how good it would be to give them electricity. Already, the well is providing irrigation for their farming endeavors, and we had run PVC to each home, giving each their own water faucet. Ladies who previously had to walk nearly four miles round trip for water now had only to step outside their front door and turn the tap. One $10,000 well project had brought their village from the first century to the twenty-first, and news of it had spread far and wide.

As one of the American pastors from Columbus, Ohio (Anchor Baptist Church) was preaching, I noticed high-power electrical lines running through the center of the village strapped to huge electric towers such as we have here in the United States. I asked Pastor Shaukat if we might be able to tap into them and provide electricity (or at least lights) to every home. These are now our brothers and sisters, following Christ wholeheartedly, so I want to bless them as best we can.

But my question brought an unexpected response. “No, brother, we cannot do that. The government will not allow Hindu villages to have electricity.” To this, I responded, “But they are no longer Hindus. They are Christians. This is a Christian village now.”

Then, Pastor Shaukat’s countenance took on a familiar grin with a sparkle in his eyes. I knew he had a brilliant idea, and he said, “You are right. I will go to the government office, and in every village that has converted, I will re-register them as a Christian village, and they will be allowed to have electricity.” (This is currently being done.)

Incidentally, there is a small percentage of Marwari who are Muslim and have denounced the Hinduism and Animism of their tribe. Those who are Hindu or Christian are nonetheless influenced by the culture’s Islamic influence. Christians in the West should understand that we, too, are influenced by past religious dominations. Such holidays (or dates of) like Christmas, Easter, Halloween, etc., have their roots in pagan celebrations but were “adapted” to be (or appear to be) Christian in modern society. We no longer worship the pagan gods, but their influence is engrained in our culture.

Reaching the Marwari in Pakistan is the key to reaching the Marwari in India. Traditionally, northwest India is the most difficult region to evangelize. Many preachers have left the South to move their families into the region for that very purpose. Many indigenous mission organizations in India have been formed solely to reach the northwest region. What we see now is that the Pakistani Marwari, having no barrier to keep them from crossing into India, are fully capable of taking the gospel to their tribal cousins living beyond the border. And they are doing just that.

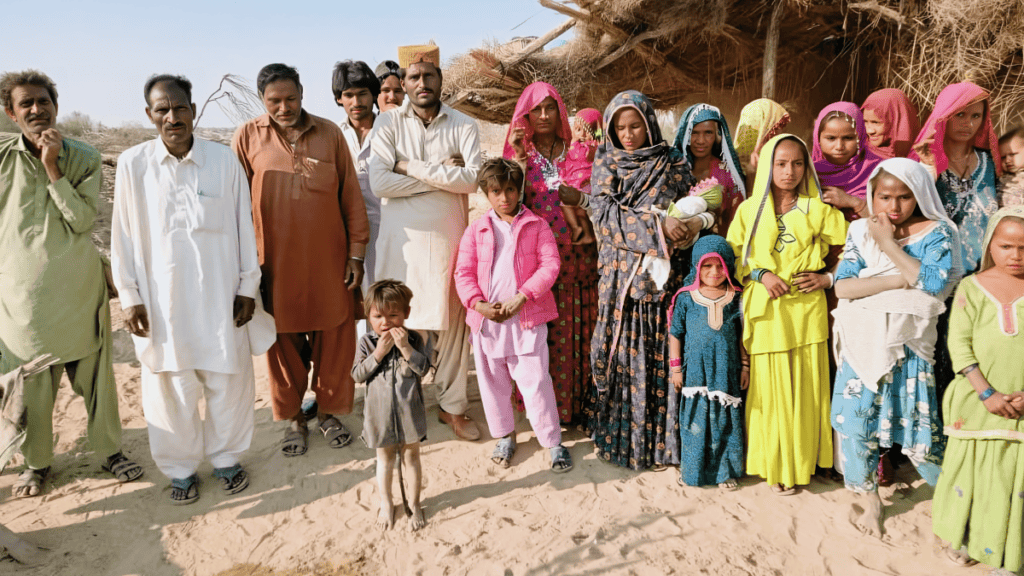

New converts in a small village

How do the Marwari Live?

Pakistan has between seventy and eighty languages; typically, the Marwari speak three: Sindhi, Urdu, and Marwari. They may live in a city area, but most live in the surrounding deserts. Their existence depends on farming seasonal crops like wheat, millet, rice, corn, and cotton. While most are farmers, others tan leather or work in cotton mills and the wool industry.

The Marwari are intrigued by those who come to visit them as they have little self-esteem. It is typical that they will serve you hot tea with goat milk but have little to offer beyond that. Their family structure is patriarchal, with very little authority given to females. Daughters are considered a burden to the family’s economy, just as they typically are in Hindu societies. Young boys and girls, from the age of three to seven, are often pledged in arranged marriages. It is widely believed that the fathers have the family’s best interest in mind when they negotiate such marriages and not the well-being or happiness of the child. A great deal of time, thought, and preparation is given to coordinate such unions, and after the ceremony, the young couple typically lives with the groom’s family.

In February 2022, in one of their villages, I met a seven-year-old boy who was already married to a five-year-old girl in a nearby village. He said he had met her once, and she was pretty. It may be another decade or longer before the ceremony takes place, but they are already married in their minds, hearts, traditions, and tribal culture.

Mary was already married (espoused) to Joseph before Christ was born, and yet, they were not married as American culture defines the term. That is why they could travel as a married couple without a negative stigma. Being promised was the same as being married in that the contract was irrevocably sealed when Joseph’s family and Mary’s family settled it. It could only have been broken if Mary had been unfaithful (even before the ceremony). For such an act, Joseph would have been released from the contract and have legal recourse for her punishment or execution. In some cultures, the engagement is as much “being married” as being married is. Marriage is, after all, a legal and binding contract.

Our Marwari Strategy:

Our goal is to fully evangelize the Marwari tribe inside Pakistan and enable them to take the gospel across the border into India. As we plant churches, we give each converted family a Bible and begin systematic training, enabling them to become mature in their faith and zealous in their witness. We never evangelize a village and abandon them. Every new congregation needs a pastor, and so we give them one. As their remaining villages, hundreds of them, begin to hear rumors of their people destroying their ancient idols and worshipping the True God, the Living God, the God who sacrificed His Son for their sins, curiosity swells, giving an open door to our national evangelists and missionaries.

It is a slow process at the beginning, but as you start training one, two, five, ten men in each village, soon they will be evangelizing one, two, five, ten villages — and teaching those converts what they have been taught. This is the pattern Paul gave to Timothy, and it works. The spiritual conquest of the Marari villages is accomplished exponentially.

As a Hindu/Animistic Marwari, when all you have ever known are gods who hate, not love; gods who take, not give; gods who destroy, not restore; gods who demand your sacrifice, rather than sacrificing His Son, you are open and eager to abandon your weak gods for the security and strength of the Living God. In Pakistan, there is a story that describes a ritual the Marwari practice when someone dies. The people give from their small supply of wheat, mix it with water, and roll it to form balls. They leave the balls outside the deceased’s house for the crows to feast on. They believe that if the crows eat the balls, it signifies that the dead person’s spirit is in torment. When I first heard this, I was perplexed at their hopelessness. Of course, the birds would eat the wheat balls; it’s logical. Thus, to the Marwari, every member of their tribe who dies is taken to a place of torment. They have no hope. But then I heard that there have been occasions of a Christian dying. The family and villagers perform the ritual, but to their surprise, the birds don’t touch the food. This tells them, “There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus.” (Romans 8:1)

Imagine entering a village and sharing this hope with them. How intently they listen, how easily they convert, how eagerly they read the Bibles we give them, seeking more good news, and how energetically they take the “good news” to the next village where their brother, sister, or parent lives. This process is expedited and exaggerated when we enter with a Jesus film in their language, and the entire village comes out to see the first motion picture of their life.

So then, to accomplish our goal, we must ask:

“How then shall they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard? And how shall they hear without a preacher? And how shall they preach, except they be sent? As it is written, “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace and bring glad tidings of good things!” (Romans 10:14-16)

The answer is – the Great Commission Fund.